Yanick Rice Lamb and her father, the late William Rice, at President Obama’s Mid-Atlantic Ball in 2009. Photo by Ingrid Sturgis.

Sibling rivalry was never really a problem for me, but all that changed when my father stood me up for Thanksgiving. On the eve of Turkey Day, I developed a case of Obama envy.

You’ve heard of “outside children?” Well, President Barack Obama has an outside family. He has two dads: Barack Hussein Obama Sr. and a surrogate, William Radford Rice, the father he “stole” from me during his first run for the White House. Daddy Rice helped him get there. Like any good father, he always believed that Barack was “The One.” He talked about him incessantly and told everyone he would become the first black president of the United States. Daddy had been saying this long before Barack’s run for Congress, breakout speech at the Democratic National Convention in 2004 and radio rebuttal to one of President Bush’s weekly radio spiels.

After Barack blindsided Hillary Clinton and John Edwards during the Iowa Democratic Caucuses in early 2008, it was on. You couldn’t tell Daddy a thing about any other presidential candidate. Daddy loved to debate, and Barack had given him more ammunition to shoot holes into any political argument. It was all Barack, all the time. He was never home when I called him, especially after he helped to open my brother Barack’s campaign office in Albany, Georgia.

After Barack blindsided Hillary Clinton and John Edwards during the Iowa Democratic Caucuses in early 2008, it was on. You couldn’t tell Daddy a thing about any other presidential candidate. Daddy loved to debate, and Barack had given him more ammunition to shoot holes into any political argument. It was all Barack, all the time. He was never home when I called him, especially after he helped to open my brother Barack’s campaign office in Albany, Georgia.

Small in stature at 5 feet, 4 inches, Daddy was gifted with an outsized personality, a giving, enthusiastic heart, and a warm, ready smile. Although he was pushing 80, no one worked harder campaigning for Barack in Southwest Georgia. Fellow campaign volunteers described him as a tireless worker who joyfully put up signs, knocked on doors and stuffed envelopes late into the night. No matter how many hours he put in while campaigning, when someone asked how he was doing, Daddy always responded “I’m Obama well!” Fluent in six languages, Daddy got a kick out of using his linguistic skills to sell Georgians on his adopted son and to tell them “Yes, we can!” in Spanish, German, French, Portuguese or Russian.

Truth be told, Daddy always treated me like “The One,” too. Even with the addition of Barack, he had more than enough fatherly pride to pass around. To hear him tell it, his children could almost walk on water. I half expected people to look for a cape on my back whenever I visited or traveled with him, because he made us sound larger than life. Coupled with my mother’s unwavering support, I grew up believing that I could do and be anything. So Barack is lucky that he was running against Hillary and not me.

Daddy’s ability to instill such confidence is all the more remarkable since I didn’t grow up with him. He and my mother divorced when I was about four, so our relationship consisted primarily of annual visits, long-distance phone calls, cards and letters. I have one very faint memory of him in our home on Grant Street, before urban renewal forced us out for a new highway and post office. For a long time, Daddy felt more like an uncle. With so many miles separating us between Albany and Akron, Ohio, I grew closer to my paternal grandfather and my stepfather. Still, we had an unbreakable bond. After all, he would say, I was his firstborn—a present that arrived two days before his 28th birthday.

Without any discussion, we began working harder on our relationship as more time, and more relatives, passed. I took my second job out of college in Atlanta to be closer to Daddy, my godmother and my grandmother, who had relocated from Akron to a family home in Fort Valley, Georgia, that became one of our meeting spots. We grew closer and better acquainted as we shared more of the ordinary—a home-cooked meal, a funny TV show, a bit of outrage over some news of the day, a Sunday service to hear me trying to sing in the choir. He counseled me on everything from real estate to relationships, having missed out on the loves of my life in high school and college.

Getting to know Daddy as an adult was like peeling an onion and discovering new layers. Sometimes he’d simply validate what I already knew or had heard, like his brilliance. He loved to travel. He loved to talk. He loved to dance. He loved to laugh. He loved to learn—not surprising for a college professor who retired years ago from Albany State University, but never left the classroom. He never stopped teaching English and foreign language. He loved students, and they loved him.

Daddy could discuss any topic, captivate anyone’s attention and fit in any environment. At a Brazilian restaurant in midtown Manhattan, I watched him astonish waiters and patrons with lively discussions in Portuguese. At family reunions, I’d crack up watching him Tootsie Roll with young cousins in Florida or show me up on the dance floor with his “hippity-hoppity” moves. At my wedding in St. Croix, I discovered that he could play the piano when he serenaded my then husband and me with an international medley.

I saw Daddy through new eyes after the birth of my son. It warmed my heart to witness the full range of his love, from the baby talk to the man-to-man talks. Their love was unconditional and untainted by the he said-she said drama of divorce that I experienced, laced with meddling by folks who mean well, but often confuse children. I remember mentioning the confusion and distance to a childhood friend, who simply responded, “At least you have a father.” Those words stuck and contributed to my resolve to make the most of my father-daughter bond. I didn’t want either of us to leave this earth with any regrets. I think we achieved that.

Much of our conversation during my father’s final year revolved around Barack Obama. Daddy was an Obama Maniac and proud of it. Barack helped Daddy go high tech as he became more interested in computers. We exchanged more emails and links to articles (about who else?) than ever before. On Election Day, he was elated, beside himself with joy like any proud father. Long before the first ballot was cast, we began discussing Inauguration Day. Logistics was a major issue given Daddy’s age, his health, the weather and parking for his small motor home. I researched options and reported back with updates by phone and email. We’d scout out locations and review all the scenarios when Daddy flew in for Thanksgiving, as I live just 25 minutes from the U.S. Capitol. And then another adopted son, Thurmond, would drive him from Georgia to Washington for the Inauguration in January.

So, somewhere in the few weeks between Election Day and Thanksgiving, Daddy put all of his eggs in the Inauguration basket and decided to make just one trip to Washington—but he forgot to tell me. I went grocery shopping for Thanksgiving, picking up supplies to make a few of Daddy’s favorite things. When I called Daddy to ask when his flight would arrive, the phone went silent. Daddy started apologizing profusely. I was confused. Daddy didn’t forget things, so I blamed it on Barack. Obama Mania made him stand me up for Thanksgiving. I wasn’t mad at Daddy. It was impossible to be mad at Daddy. And besides, it wasn’t his fault. It was my brother Barack’s fault, but I decided not to be mad at him either. Instead, I followed Daddy’s lead and went into celebration mode, especially since it was also the holiday season.

As Inauguration Day approached, temperatures in the Washington area were below freezing. It was so cold that my furnace went kaput. I started talking to Daddy about alternatives to being on the Mall, but he wasn’t hearing it. He insisted that his military gear would be enough to keep him warm. After some back and forth, we cut a deal. I’d take him to see Barack’s Whistle Stop Tour, so that he could experience the cold for a shorter length of time. If he agreed with me about the weather, he’d go to a viewing party at the home of a family friend and attend other, indoor inaugural events. Daddy thought he had options, but it was a done deal as far as I was concerned. It was too cold for him to be on the Mall. Period.

Daddy was bubbling with excitement when he arrived in Washington. “I’m Obama happy!” he told anyone within earshot. He asked me to drive by the White House even though he had seen it a zillion times. I knew the traffic would be horrendous, but there was no way that I’d deny him the view.

On the evening of the Whistle Stop Tour’s arrival, we watched TV coverage of the Baltimore stop so that we could gauge when to head to the train station in New Carrollton, Maryland, five minutes from my home. Once there, a station official announced the impending arrival of Barack’s train with great fanfare. Everyone standing along the chain-link fence cheered. At other stations, Barack’s train crawled by. But at New Carrollton, the last stop before Union Station in Washington, Barack’s train went “woosh,” zipping by as fast as the Acela with a gust of frigid air that could knock you over.

“I’ll be damned,” I muttered to a friend. “All this for that?” As a journalist and resident of a few big cities who had been there and done that, I was jaded, a little annoyed and freezing cold. But all of that faded when I looked over at my father. He was beaming. He pulled out his cell phone and rapidly punched in some numbers. “Guess what?” he told his best friend. “I just saw the president!”

Daddy proclaimed Inauguration week as a high point of his nearly 80 years. It was indeed a magical time. Over dinner in my kitchen one evening, he blessed the food with the most profound grace I’ve ever heard. Daddy always had a way with words, but this was particularly poetic. It was so amazing that I wished it had been documented for posterity. Another evening, I pulled out a video camera to record his thoughts and capture some of this moment in time. By Inauguration Day, it was still freezing, and I could see that Daddy was increasingly frail and sometimes unsteady on his feet. He finally agreed to forgo the cold and attend the viewing party, but he almost reneged at the last moment. Fortunately, he had a blast at the party and at a town hall event.

At the 11th hour, we were able to secure tickets to the Mid-Atlantic Ball. He had packed a tux, just in case. I was working with some of my Howard University students who were covering the Inauguration, so Daddy drove my car to campus. I changed into my gown while he waited in our newsroom; then we headed over to the Convention Center. Daddy is a dancing machine, but he declined to dance at the ball; he didn’t want to be out of position when Barack came through. We sat for a while, and then the crowd parted to allow Daddy to move near the stage for a better view. He stood mesmerized at the sight of the president and first lady, proclaiming Michelle Obama as “the most beautiful first lady ever.”

“What about Jackie?” I asked teasingly.

“Oh no,” Daddy said. “There’s no comparison.”

“You’re biased.”

“Absolutely!”

Daddy had literally saved all of his energy for this moment. He had been running on pure adrenalin for who knows how long. At the end of the ball, he could barely make it to the car. I requested assistance, a golf cart, an escort and permission to move my car closer, all to no avail. Security was tight, and everyone said they couldn’t leave their posts. Fortunately, Daddy rebounded enough to walk slowly to the car.

That was our last outing.

Yanick Rice Lamb shares memories of her father at a book signing in Washington, D.C. (Photo courtesy of Kenrya Rankin Naasel)

Shortly thereafter, Daddy was diagnosed with colon cancer. True to form, he planned to fight it as hard as he had fought prostate cancer. He took a break from classes to have surgery, but never fully regained his strength after the operation. We knew that he probably wouldn’t last more than a year. He wanted to attend our family reunion in South Carolina, and we were determined to get him there as comfortably as possible. We also wanted to proceed with plans for his 80th birthday celebration. He didn’t make it to either one.

Despite the pain of his passing, Daddy’s homegoing was truly a celebration of a life well lived. The stories of people who had met him at the flea market, studied in his classes or been otherwise inspired by him were truly heartwarming. People stopped my sister and me at red lights as we drove around town in Daddy’s gray station wagon, covered with Obama and Albany State stickers. They lined up to speak at his wake, where Barack’s name came up over and over again. One woman said that Daddy told her she had Hillary-itis.

We also learned from his buddies that my mother’s tales of Daddy being a spy might not be as farfetched as we thought. His 38-year military career included four years with the Strategic Air Command, including a post in Northern Africa where he worked as an interpreter while teaching Spanish and French classes. Although he never discussed it with us, he apparently gathered intelligence, too, posing as a janitor while people spoke freely around him in various languages.

We buried Daddy in the tux that he wore to Barack’s ball just three months earlier. The tickets were still in his pocket. Barack, of course, didn’t attend the funeral of the father he never knew, but his office sent a proclamation. I know that Daddy put in a good word with God to help Barack get reelected, and that he’s happy about his presidency, my tenure at Howard, my son’s graduation and my grandson’s birth. I’m sure he’s smiling, watching and bragging, talking someone’s ear off in any number of languages.

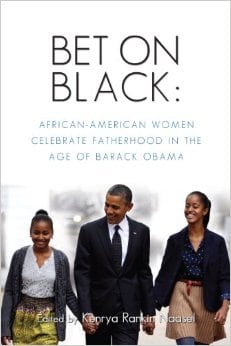

Reprinted by permission from Bet on Black: African American Women on Fatherhood in the Age of Obama edited by Kenrya Rankin Naasel (Kimani Press, 2013)

Yanick Rice Lamb, co-founder of FierceforBlackWomen.com, is an associate professor of journalism at Howard University. Her forthcoming novel is Nursing Wounds. Follow her at @yrlamb.

Recent Comments